If you are a banana lover, then you might read this article with a little worry and you are not alone. As the world’s population grows and consumption rises, the massive plantation of both fruits and vegetables hampers the plants’ abilities to develop natural resistance to muting diseases, which threatens many species with extinction.

As for bananas, the volume of worldwide production has increased in 11 years by more than 15% starting with 108.66 MT[1] in 2020 to 124.98 in 2021 which requires more resources of water, soil’s minerals, and handcraft. According to a report in the year 2019 of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the main importers of Bananas are Europe (32% of the global imports) followed by the United States (25% of the global imports) while the main exporters are Ecuador (30% of the total volume of exports), the Philippines (14% of the total volume of exports) and Costa Rica (13% of the total volume of exports). These figures clearly show the imbalance between consumption requirements and production’s capacities.

However, let us focus first on the types of bananas that we find in our local markets or supermarkets. What we know today as this long, yellow, and sweet banana is called the Cavendish and is the most commercialized type among 1,000 types of bananas. This cultivar is well appreciated by producers because it is also one of the most cost-effective since it has high yields per hectare of plantation. The Cavendish is also monoculture which means that it is reproduced via cloning, this allows a quicker and homogenous production. Yet, quicker and bigger production also means a high stress of the bananas that often do not have enough time to strengthen their resistance against diseases, especially when the cultivars are very close to each other. Parasites can then jump from a banana tree to another in uncontrolled velocity.

As risky as it may sound, “banana’s extinction” had already happened in the past with Gros Michel type. Gros Michel was also monoculture and known for the same adaptation’s capacities that are seen in the Cavendish. Unfortunately, a soil’s fungus called Panama disease, appeared in the late 1800s and spread, causing banana plants to wilt and led to great losses of Gros Michel banana’s plants. Fighting against the fungus has been very expensive for the concerned businesses and led to a rewind with a new cultivar, the Cavendish.

Although resistant to the first race of the Panama disease, a fourth race of the fungus is now seriously threatening the Cavendish which can cause the same scenario to happen in the next decade. Colombia, one of the exporters of bananas, has already announced in 2019 the state of emergency for banana plantations in its northern regions. It is not only a huge natural catastrophe, but also a big economic loss as bananas are the third-biggest agricultural export of the country. The fungus threatens the plants but also the jobs of many people who may lack the basic needs.

Now, there is no clear solution to fight this race of the Panama disease, but strict measures have started being adopted in the exporting countries to contain the spread-off. There is also the option of crossbreeding different types of bananas with the Cavendish to make it more resistant, although its tasting properties might change.

All in all, the goal of this article is not to spread worry bur rather consciousness of the fragility of nature thus, the fragility of our global ecosystem that should be taken for granted. We need more collective actions to protect all levels and actors of the food chain and at the end, to protect us.

[1] MT : Million metric tons

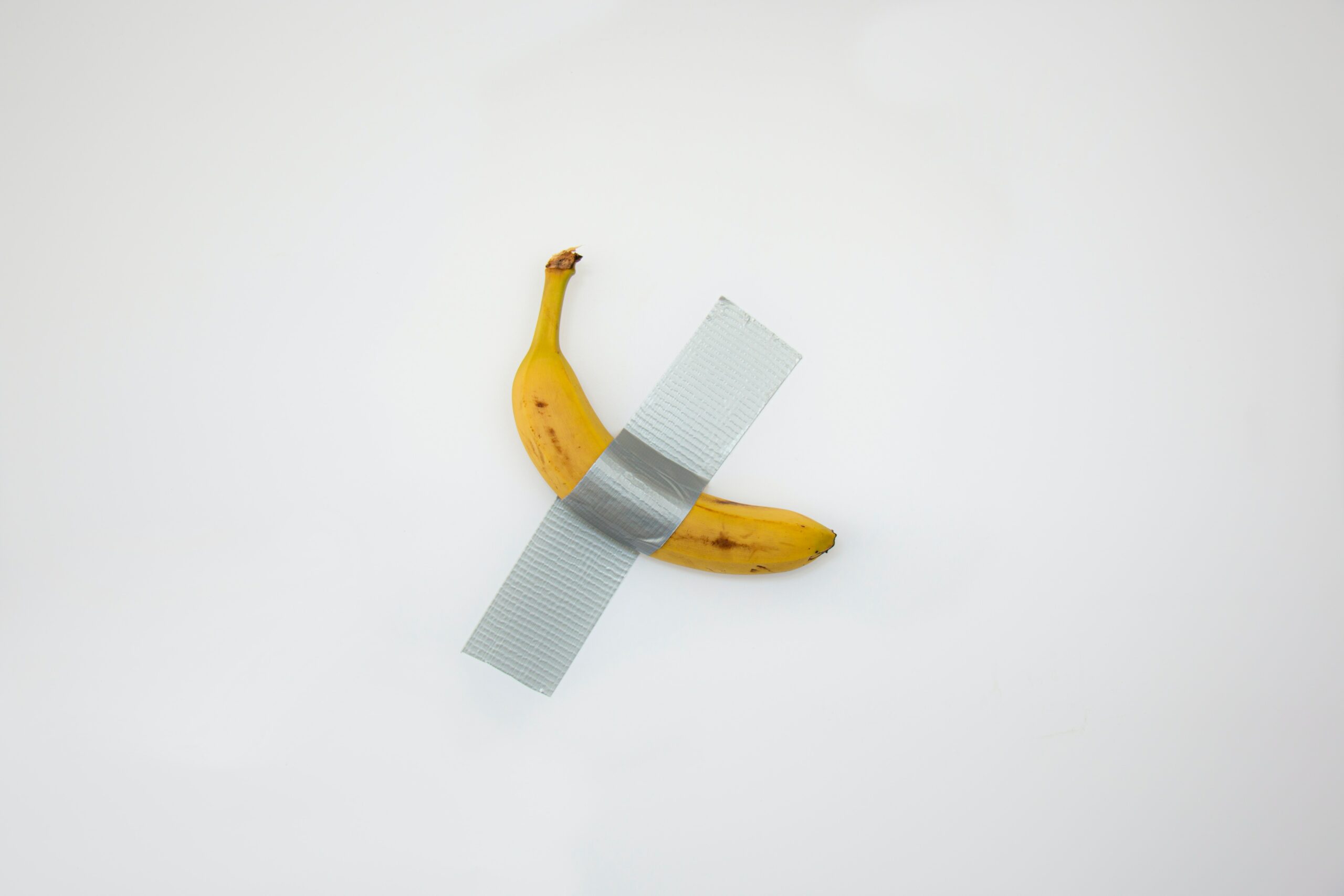

Cover Image: "Comedian", Maurizio Cattelan, 2019.