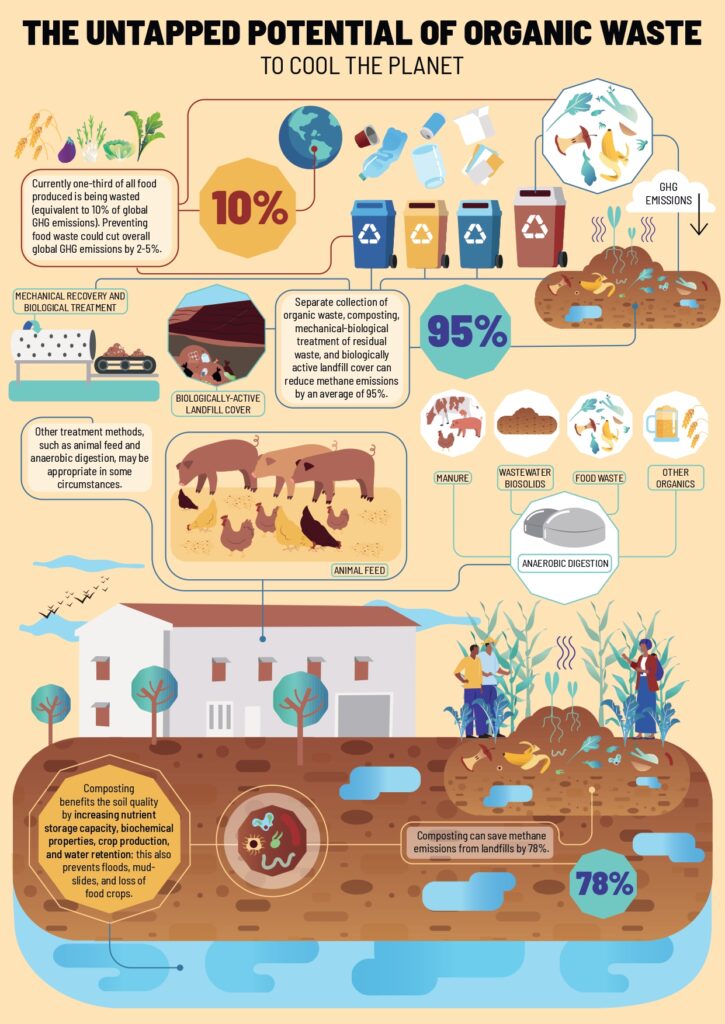

According to the World Bank, trends show that the world generates 2.01 billion tonnes of municipal solid waste annually, with at least 33% of that not managed in an environmentally safe manner. The food we throw away create many by-products, and methane is one of the worst offenders – responsible for as much as 16% of GHGs and for around 30% of the rise in global temperatures since the industrial revolution (Global Methane Tracker 2022).

«If food waste were its own country, it would be the fourth largest emitter of heat-trapping gases in the world» Katharine Hayhoe

Zero Waste to Zero Emissions – How reducing waste is a climate gamechanger, a report by the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, explains that waste management methods can help the world fight global warming, while building resilience, creating jobs, and promoting thriving local economies. Reforming the sector could cut global methane emissions by 13%.

In that sense, South Korea is an interesting and virtuous case study. As reported by Max S Kim for The Guardian, this country has cut down food waste to almost zero. How come? Thanks to its mandatory composting scheme. Since 2005, the government banned burying organic waste in landfills and, later in 2013, another ban came against dumping leachate – the putrid liquid squeezed from solid food waste. That same year, a universal curbside composting was implemented, demanding everyone to separate their food from general waste.

Residents have been required to use special bags to throw out their uneaten food. Each 3-liter bag costs 300 won (about 20 cents). The bags are then hauled off to a processing plant, where the plastics is stripped off and its contents recycled into biogas, animal feed or fertilizer. Some municipalities have also introduced automated food waste collectors in apartment complexes. Here comes the result: in 1996, South Korea recycled just 2.6% of its food waste – today, the recycling rate is close to 100% annually.

The model happened to be successful because it is ease-of-use and accessible: «South Korea’s waste system, especially in terms of frequency of collection, is incredibly convenient compared to other countries,» says Hong Su-yeol, a waste expert and director of Resource Recycling Consulting. «Some of my peers working at non-profits overseas say that disposal should be a little bit inconvenient if you want to discourage waste but I disagree: I think that it should be made as easy as possible as long as it goes hand-in-hand with other policies that attack the problem of reducing waste itself».

In addition, it is important to highlight the importance of balancing cost-sharing and affordability. Food waste transportation is expensive, due to its heaviness – the revenue from the bags is collected by the district government to help defray the costs of this process: «As long as the public’s sense of civic duty can accommodate it, I think it’s good to charge a fee for food waste […] But if you make it so costly that people feel the blow, they’re going to throw it away illegally».

However, Max S Kim (The Guardian) explains that there are also some breaking points. The viability of recycled food waste as animal feed has been undermined by livestock diseases, while fertilizer made from compost has struggled to find takers even among the farmers.

As well as there is a need for more diversified recycling and end-use streams, it is also important to foster an intensive communication. National and municipal governments have been investing in urban farming programs, including composting courses and projects grants. As Hong stated: «we need more efforts to compost at the source, expanding many smaller models driven by resident participation rather than relying only on mass processing».

In short: environmental education and pro-activeness are fundamental to strengthen a system which is based on a successful scheme, but it is also important to choose a narrative of reduction and prevention at the source. Each individual need to look at waste as an opportunity to redefine habits and get more and more conscious about the damage of uncontrolled consumption.