The universe is incredible and incredibly complex. So is the world of science. It is thus no wonder that people are confused when scientists talk about their work. Unless we belong to the same field of research, we are likely to be confused too.

As scientists, we spend our time researching and learning all about a very specific topic in our field and are trained in how to tell other scientists all about it. We learn to read complex studies published by others and to write our own in a similarly complex and technical way. We are also taught how to speak to other scientists in similar fields, to make presentations and posters for conferences and, if we are lucky, even how to write briefs for policy makers. However, nobody teaches us how to talk to the general public, even though sharing our knowledge in an understandable way is vital so that we are all, as a society, better equipped to combat the climate and biodiversity crisis.

Now on the verge of finishing my master’s degree in marine microbiology, I have never received any such instruction. All that I have learnt on this subject, I have gathered through my own interest in it and actively getting involved with outreach in my free time. Part of my learning came from attending a seminar on storytelling as a tool for science communication given by Dr. Helen Spence-Jones from the Alfred-Wegener-Institute on Sylt (Germany) during my internship at the institute last spring.

Dr. Spence-Jones is currently a postdoc in the working group “Community & Evolutionary Ecology”, non-genetic inheritance and adaptation to temperature variation and heatwaves in threespine sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus). Furthermore, she is an author and freelance illustrator in her spare time.

Storytelling as a tool for science communication

Dr. Spence-Jones emphasised the importance of telling a story when communicating science, as stories are a way to repackage complex information and make it understandable and easy to remember.

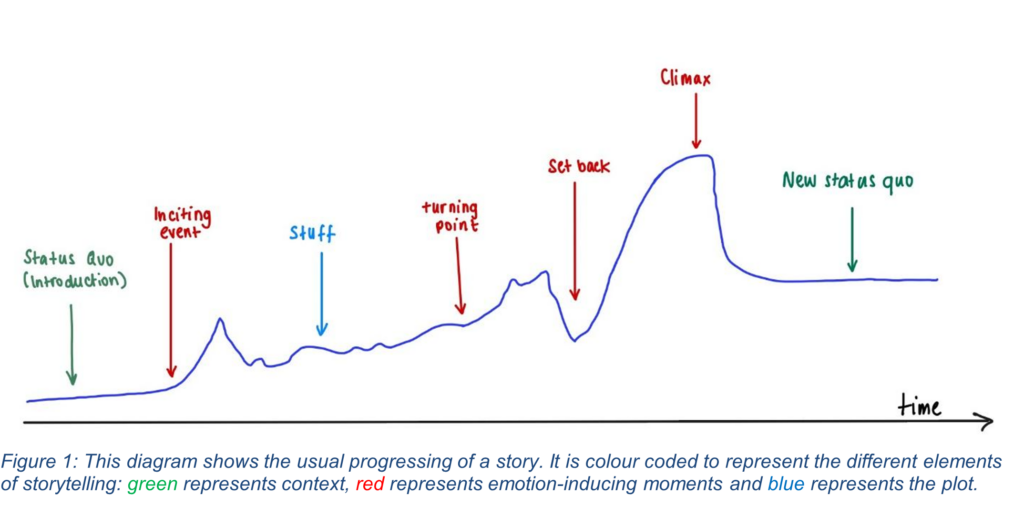

First of all, we need to find our “narrative”, or what shape our story is going to take. We need to create a path through our messy reality and guide the audience through it. We need to narrow our focus and concentrate only on one path, to avoid it becoming overwhelming. Then, with it we create the basic story structure:

Status quo → Inciting event/ problem → Trying to solve it → Resolution

This is also illustrated in the following figure:

Elements of a story and narrative style

There are four different elements of a story and how you choose to use them should be based on the type of audience you address and what effect you would like to have on them.

- Context or world building. This provides context for the audience to follow your story and should include familiar things for the audience to be able to fit your story in their worldview and understand it. When introducing them to the topic, you should use the inverted triangle approach: start from the big picture and then progress to the narrower focus of your research.

- Action or plot. Just like in any good action movie, your story needs to be full of events and developments. Tell them about the process that led to your discovery, making sure to pace the development evenly. You can introduce an antagonist to the story, i.e. mishaps and set-backs in your work. This will get the audience interested, excited and more likely to follow you as you lead them through your story.

- Emotions. Us humans are good at empathising with others, so using emotions as part of science communication gets the audience invested and makes them remember your story. Use a shared experience to allow them to feel like the hero and bring them along the journey as your co-hero. Let them experience both positive and negative emotions, but try to end on a positive note.

- Mystery. Everyone likes feeling smart and your audience is the same. Engage your audience with unanswered questions, foreshadowing and unexpected outcomes of a known path. This is another way to get them involved and make them feel like part of your story.

Pitching the story

The most important thing to remember when using these tips is that the audience needs to leave the room thinking that:

- They are smart.

- You think that they are smart.

- You are smart, but not too smart. Otherwise, the audience may feel alienated.

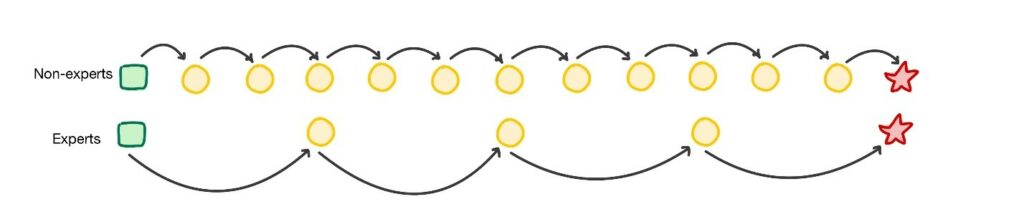

To achieve this, it is important that you identify the audience’s previous knowledge and build on it without giving them all the answers. You want to give them gaps that you are confident they can fill in themselves.

The importance of storytelling

We humans are born storytellers and stories are how we best understand, process and recall information. Although this is not common practice, perhaps introducing storytelling techniques in science communication is the key to make science more accessible and engaging for everyone.

Because after all, your science is a story worth telling.

Cover image: © 2020 She Speaks Science